- Home

- Pushkin, Alexander

B007GZKQTC EBOK

B007GZKQTC EBOK Read online

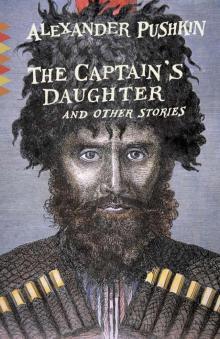

ALEXANDER PUSHKIN

THE CAPTAIN’S DAUGHTER

and Other Stories

Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837) was a writer, poet, and playwright of the Romantic era who pioneered the use of vernacular speech in Russian literature. He was descended from Russian nobility and from an African great-grandfather who had been raised at the court of Peter the Great. Pushkin’s commitment to social reform led him to suffer a period of exile and government censorship, during which he wrote some of his most famous works. He died after fighting a duel at the age of thirty-seven.

FIRST VINTAGE CLASSICS EDITION, AUGUST 2012

Compilation copyright © 1957 by Random House, Inc.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. This edition was originally published in paperback in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 1957.

“The Captain’s Daughter” was translated by Natalie Duddington. The other stories in this volume were translated by T. Keane.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Classics and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

eISBN: 978-0-307-94966-0

Cover design by Megan Wilson

Front cover art: Cossack of the Don, 1880s, Russian School / Private Collection / Peter Newark Military Pictures / The Bridgeman Art Library

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Title Page

Copyright

THE CAPTAIN’S DAUGHTER

THE TALES OF BELKIN

THE SHOT

THE SNOWSTORM

THE UNDERTAKER

THE POSTMASTER

MISTRESS INTO MAID

THE QUEEN OF SPADES

KIRDJALI

THE NEGRO OF PETER THE GREAT

The Captain’s Daughter

Watch over your honor while you are young …

A PROVERB

I

A SERGEANT OF THE GUARDS

He would have been a Captain in the Guards tomorrow.

“I do not care for that; a common soldier let him be.”

A splendid thing to say! He’ll have much sorrow …

Who is his father, then?

KNYAZHNIN

My father, Andrey Petrovich Grinyov, had in his youth served under Count Münnich and retired with the rank of first major in the year 17—. From that time onward he lived on his estate in the province of Simbirsk, where he married Avdotya Vassilyevna U., daughter of a poor landowner of the district. There had been nine of us. All my brothers and sisters died in infancy. Through the kindness of Prince B., our near relative, who was a major of the Guards, I was registered as sergeant in the Semyonovsky regiment. I was supposed to be on leave until I had completed my studies. Our bringing-up in those days was very different from what it is now. At the age of five I was entrusted to the groom Savelyich, who was assigned to look after me, as a reward for the sobriety of his behavior. Under his supervision I had learned, by the age of twelve, to read and write Russian, and could judge very soundly the points of a borzoi dog. At that time my father hired for me a Frenchman, Monsieur Beaupré, who was fetched from Moscow together with a year’s supply of wine and olive oil. Savelyich very much disliked his coming.

“The child, thank heaven, has his face washed and his hair combed, and his food given him,” he grumbled to himself. “Much good it is to spend money on the Frenchman, as though the master hadn’t enough servants of his own on the estate!”

In his native land Beaupré had been a hairdresser; afterward he was a soldier in Prussia, and then came to Russia pour être outchitel,* without clearly understanding the meaning of that word. He was a good fellow, but extremely thoughtless and flighty. His chief weakness was his passion for the fair sex; his attentions were often rewarded by blows, which made him groan for hours. Besides, “he was not an enemy of the bottle,” as he put it; that is, he liked to take a drop too much. But since wine was only served in our house at dinner, and then only one glass to each person, and the tutor was generally passed over, my Beaupré soon grew accustomed to the Russian homemade brandy and, indeed, came to prefer it to the wines of his own country as being far better for the digestion. We made friends at once, and although he was supposed by the agreement to teach me “French, German, and all subjects,” he preferred to pick up some Russian from me and, after that, we each followed our own pursuits. We got on together capitally. I wished for no other mentor. But fate soon parted us, and this was how it happened.

The laundress, Palashka, a stout pock-marked girl, and the dairymaid, one-eyed Akulka, had agreed to throw themselves together at my mother’s feet, confessing their culpable weakness and tearfully complaining of the mossoo who had seduced their innocence. My mother did not like to trifle with such things and complained to my father. My father was not one to lose time. He sent at once for that rascal, the Frenchman. They told him mossoo was giving me my lesson. My father went to my room. At that time Beaupré was sleeping the sleep of innocence on the bed; I was usefully employed. I ought to mention that a map of the world had been ordered for me from Moscow. It hung on the wall; no use was made of it, and I had long felt tempted by its width and thickness. I decided to make a kite of it and, taking advantage of Beaupré’s slumbers, set to work upon it. My father came in just at the moment when I was fixing a tail of tow to the Cape of Good Hope. Seeing my exercises in geography, my father pulled me by the ear, then ran up to Beaupré, roused him none too gently, and overwhelmed him with reproaches. Covered with confusion, Beaupré tried to get up but could not: the unfortunate Frenchman was dead drunk. He paid all scores at once: my father lifted him off the bed by the collar, kicked him out of the room, and sent him away that same day, to the indescribable joy of Savelyich. This was the end of my education.

I was allowed to run wild, and spent my time chasing pigeons and playing leap-frog with the boys on the estate. Meanwhile I had turned sixteen. Then there came a change in my life.

One autumn day my mother was making jam with honey in the drawing room, and I licked my lips as I looked at the boiling scum. My father sat by the window reading the Court Calendar, which he received every year. This book always had a great effect on him: he never read it without agitation, and the perusal of it invariably stirred his bile. My mother, who knew all his ways by heart, always tried to stow the unfortunate book as far away as possible, and sometimes the Court Calendar did not catch his eye for months. When, however, he did chance to find it, he would not let it out of his hands for hours. And so my father was reading the Court Calendar, shrugging his shoulders from time to time and saying in an undertone: “Lieutenant-General!… He was a sergeant in my company … a Companion of two Russian Orders!… And it isn’t long since he and I …”

At last my father threw the Calendar on the sofa, and sank into a thoughtfulness which boded nothing good.

He suddenly turned to my mother: “Avdotya Vassilyevna, how old is Petrusha?”

“He is going on seventeen,” my mother answered. “Petrusha was born the very year when Auntie Nastasya Gerasimovna lost her eye and when …”

“Very well,” my father interrupted her; “it is time he went into the service. He has been running about the servant-girls’ quarters and climbing dovecotes long enough.”

My mother was so overwhelmed at the thought of

parting from me that she dropped the spoon into the saucepan and tears flowed down her cheeks. My delight, however, could hardly be described. The idea of military service was connected in my mind with thoughts of freedom and of the pleasures of Petersburg life. I imagined myself as an officer of the Guards, which, to my mind, was the height of human bliss.

My father did not like to change his plans or to put them off. The day for my departure was fixed. On the eve of it my father said that he intended sending with me a letter to my future chief, and asked for paper and a pen.

“Don’t forget, Andrey Petrovich, to send my greetings to Prince B.,” said my mother, “and to tell him that I hope he will be kind to Petrusha.”

“What nonsense!” my father answered, with a frown. “Why should I write to Prince B.?”

“Why, you said you were going to write to Petrusha’s chief.”

“Well, what of it?”

“But Petrusha’s chief is Prince B., to be sure. Petrusha is registered in the Semyonovsky regiment.”

“Registered! What do I care about it? Petrusha is not going to Petersburg. What would he learn if he did his service there? To be a spendthrift and a rake? No, let him serve in the army and learn the routine of it and know the smell of powder and be a soldier and not a fop! Registered in the Guards! Where is his passport? Give it to me.”

My mother found my passport, which she kept put away in a chest together with my christening robe, and, with a trembling hand, gave it to my father. My father read it attentively, put it before him on the table, and began his letter.

I was consumed by curiosity. Where was I being sent if not to Petersburg? I did not take my eyes off my father’s pen, which moved rather slowly. At last he finished, sealed the letter in the same envelope with the passport, took off his spectacles, called me and said: “Here is a letter for you to Andrey Karlovich R., my old friend and comrade. You are going to Orenburg to serve under him.”

And so all my brilliant hopes were dashed to the ground! Instead of the gay Petersburg life, boredom in a distant and wild part of the country awaited me. Going into the army, of which I had thought with such delight only a moment before, now seemed to me a dreadful misfortune. But it was no use protesting! Next morning a traveling chaise drove up to the house; my bag, a box with tea things, and bundles of pies and rolls, the last tokens of family affection, were packed into it. My parents blessed me. My father said to me: “Good-bye, Pyotr. Carry out faithfully your oath of allegiance; obey your superiors; don’t seek their favor; don’t put yourself forward, and do not shirk your duty; remember the saying: ‘Watch over your clothes while they are new, and over your honor while you are young.’ ”

My mother admonished me with tears to take care of myself, and bade Savelyich look after “the child.” They dressed me in a hareskin jacket and a fox-fur overcoat. I stepped into the chaise with Savelyich and set off on my journey, weeping bitterly.

In the evening I arrived at Simbirsk, where I was to spend the next day in order to buy the things I needed; Savelyich was entrusted with the purchase of them. I put up at an inn. Savelyich went out shopping early in the morning. Bored with looking out of the window into the dirty street, I wandered about the inn. Coming into the billiard room I saw a tall man of about thirty-five, with a long black mustache, in a dressing-gown, a billiard cue in his hand, and a pipe in his mouth. He was playing with the marker, who drank a glass of vodka on winning and crawled under the billiard table on all fours when he lost. I watched their game. The longer it continued, the oftener the marker had to go on all fours, till at last he remained under the table altogether. The gentleman pronounced some expressive sentences by way of a funeral oration and asked me to have a game. I refused, saying I could not play. This seemed to strike him as strange. He looked at me with something like pity; nevertheless, we entered into conversation. I learned that his name was Ivan Ivanovich Zurin, that he was captain of a Hussar regiment, that he had come to Simbirsk to receive recruits, and was staying at the inn. Zurin invited me to share his dinner, such as it was, like a fellow-soldier. I readily agreed. We sat down to dinner. Zurin drank a great deal and treated me, saying that I must get used to army ways; he told me military anecdotes, which made me rock with laughter, and we got up from the table on the best of terms. Then he offered to teach me to play billiards.

“It is quite essential to us soldiers,” he said. “On a march, for instance, one comes to some wretched little place; what is one to do? One can’t be always beating Jews, you know. So there is nothing for it but to go to the inn and play billiards; and to do that one must be able to play!”

He convinced me completely and I set to work very diligently. Zurin encouraged me loudly, marveled at the rapid progress I was making, and after several lessons suggested we should play for money, at a penny a point, not for the sake of gain, but simply so as not to play for nothing, which, he said, was a most objectionable habit. I agreed to this, too, and Zurin ordered some punch and persuaded me to try it, repeating that I must get used to army life; what would the army be without punch! I did as he told me. We went on playing. The oftener I sipped from my glass, the more reckless I grew. My balls flew beyond the boundary every minute; I grew excited, abused the marker, who did not know how to count, kept raising the stakes—in short, behaved like a silly boy who was having his first taste of freedom. I did not notice how the time passed. Zurin looked at the clock, put down his cue, and told me that I had lost a hundred rubles. I was somewhat taken aback. My money was with Savelyich. I began to apologize; Zurin interrupted me: “Please do not trouble, it does not matter at all. I can wait; and meanwhile let us go and see Arinushka.”

What can I say? I finished the day as recklessly as I had begun it. We had supper at Arinushka’s. Zurin kept filling my glass and repeating that I ought to get used to army ways. I could hardly stand when we got up from the table; at midnight Zurin drove me back to the inn.

Savelyich met us on the steps. He cried out when he saw the unmistakable signs of my zeal for the Service.

“What has come over you, sir?” he said in a shaking voice, “wherever did you get yourself into such a state? Good Lord! Such a dreadful thing has never happened to you before!”

“Be quiet, you old dodderer!” I mumbled. “You must be drunk; go and lie down … and put me to bed.”

Next day I woke up with a headache, vaguely recalling the events of the day before. My reflections were interrupted by Savelyich, who came in to me with a cup of tea.

“It’s early you have taken to drinking, Pyotr Andreyich,” he said to me, shaking his head, “much too early. And whom do you get it from? Neither your father nor your grandfather were drunkards; and your mother, it goes without saying, never tastes anything stronger than kyass. And who is at the bottom of it all? That damned Frenchman. He kept running to Antipyevna: ‘Madame, she voo pree vodka.’ Here’s a fine ‘shu voo pree’ for you! There is no gainsaying it, he has taught you some good, the cur! And much need there was to hire an infidel for a tutor! As though Master had not enough servants of his own!”

I was ashamed. I turned away and said to him: “Leave me, Savelyich, I don’t want any tea.” But it was not easy to stop Savelyich once he began sermonizing.

“You see now what it is to take too much, Pyotr Andreyich. Your head is heavy, and you have no appetite. A man who drinks is no good for anything…. Have some cucumber brine with honey or, better still, half a glass of homemade brandy. Shall I bring you some?”

At that moment a servant-boy came in and gave me a note from Zurin.

Dear Pyotr Andreyich,

Please send me by my boy the hundred rubles you lost to me at billiards yesterday. I am in urgent need of money.

Always at your service,

Ivan Zurin

There was nothing for it. Assuming an air of indifference I turned to Savelyich, “the keeper of my money, linen, and affairs,” and told him to give the boy a hundred rubles.

“What! Why should I giv

e it to him?”

“I owe it to him,” I answered, as coolly as possible.

“Owe it!” repeated Savelyich, growing more and more amazed. “But when did you have time to contract a debt, sir? There’s something wrong about this. You may say what you like, but I won’t give the money.”

I thought that if at that decisive moment I did not get the better of the obstinate old man, it would be difficult for me in the future to free myself from his tutelage, and so I said, looking at him haughtily: “I am your master, and you are my servant. The money is mine. I lost it at billiards because it was my pleasure to do so; and I advise you not to argue, but to do as you are told.”

Savelyich was so startled by my words that he clasped his hands and remained motionless.

“Well, why don’t you go?” I cried angrily.

Savelyich began to weep.

“My dear Pyotr Andreyich,” he said, in a shaking voice, “do not make me die of grief. My darling, do as I tell you, old man that I am; write to that brigand that it was all a joke, and that we have no such sum. A hundred rubles! Good Lord! Tell him that your parents have strictly forbidden you to play unless it be for nuts …!”

“That will do,” I interrupted him sternly; “give me the money or I will turn you out.”

Savelyich looked at me with profound grief and went to fetch the money. I was sorry for the poor old man, but I wanted to assert my independence and to prove that I was no longer a child.

The money was delivered to Zurin. Savelyich hastened to get me out of the accursed inn. He came to tell me that horses were ready. I left Simbirsk with an uneasy conscience and silent remorse, not saying good-bye to my teacher and not expecting ever to meet him again.

II

THE GUIDE

Thou distant land, land unknown to me!

Not of my will have I come to thee,

B007GZKQTC EBOK

B007GZKQTC EBOK